I’m always delighted to connect with other Ancient World authors, especially fellow Romaphiles. My trilogy deals with Rome’s war with the mysterious Etruscans but there was another famous civilization which fought the Romans in early Republican times. Kate Q. Johnson joins me today with a post on the famous struggle between Rome and Carthage.

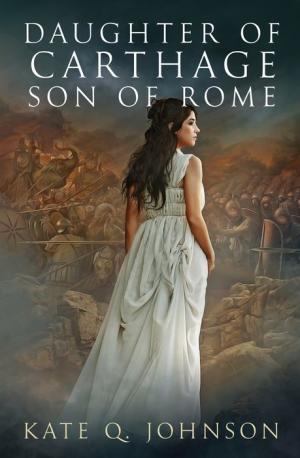

Kate is a writer, scientist and academic who doesn’t believe in following only one dream. Moonlighting as a romance writer while completing her PhD in Pharmaceutical Sciences, it was her love of history that compelled her to write her debut novel, Daughter of Carthage, Son of Rome. Fueled by caffeine and croissants at 24-hour cafes, Kate brings the epic wars and earth-shattering events of Ancient Rome to life for a modern audience. She lives in Seattle with her husband and new baby, where she is probably multitasking with a cup of coffee. Follow along at kqjohnson.com, and on Twitter @kqjohnwrites.

Kate is a writer, scientist and academic who doesn’t believe in following only one dream. Moonlighting as a romance writer while completing her PhD in Pharmaceutical Sciences, it was her love of history that compelled her to write her debut novel, Daughter of Carthage, Son of Rome. Fueled by caffeine and croissants at 24-hour cafes, Kate brings the epic wars and earth-shattering events of Ancient Rome to life for a modern audience. She lives in Seattle with her husband and new baby, where she is probably multitasking with a cup of coffee. Follow along at kqjohnson.com, and on Twitter @kqjohnwrites.

You can find Daughter of Carthage, Son of Rome on Amazon, Barnes and Noble, Kobo, Google Play and on Apple Books.

A Lost Civilization

History is written by the victors is an oft-repeated phrase, but one that grows truer with time. On its path from small city-state to conquerors of most of the western world, countless civilizations were lost to Roman hegemony. Many of these civilizations were extremely advanced, with unique cultures, religion, and technology. As an empire, Rome tended to be relatively lenient with the peoples it conquered (with some very notable exceptions – see Julius Caesar and the Gauls). Provided they paid taxes and contributed militarily, local governments were often left intact. But for those opponents who managed to truly threaten Rome’s existence, or who lodged themselves in the Roman psyche in a way that altered the complexion of their society, there were few victors more ruthless than the Romans.

The Carthaginians

Carthage was a coastal city on the northern tip of Africa (modern day Tunisia). It was founded in 800 BCE by Phoenicians, a Semitic sea people who prospered following the Bronze Age collapse. Carthage grew rapidly in wealth and importance due to its naval prowess and location along lucrative Mediterranean trade routes. The Carthaginians were famous for their purple dye, which they manufactured using Phoenician techniques and distributed throughout the Mediterranean. Often used for ceremonial robes, it was one of the most highly valued commodities in the ancient world, worth many times its weight in gold. By 300 BCE Carthage was a wealthy superpower, with vast territories in northern Africa, southern Spain, Sardinia and Sicily, and a virtual monopoly over maritime traffic in the Mediterranean. In hindsight, a clash with the upstart city of Rome was inevitable.

The Punic Wars

Rome and Carthage fought three wars between 264 and 146 BCE, collectively known as the Punic Wars. At the start of the First Punic War, Rome was still an emerging power in the Mediterranean, having only recently subdued the entire Italian peninsula after centuries of war with the Samnites (–290 BCE) and Etruscans (–265 BCE). The First Punic War lasted from 264–241 BCE and involved some of the greatest naval battles of antiquity, with hundreds of thousands dead on both sides. After a 23-year war of attrition fought mostly in Sicily, the Carthaginians bitterly accepted a peace treaty that resulted in the loss of their territories in Sicily and Sardinia, and humiliating reparations to Rome.

The economic and military defeat of Carthage proved temporary. Although they had lost their dominance over the seas, the Carthaginians quickly expanded their territory in Iberia (modern Spain) through the campaigns of Hamilcar Barca, father of the famous Hannibal. Once again flooded with riches, the Carthaginians chafed under Roman treaty conditions. The fortunes of the Barca family continued to rise, and it was the brilliant young general, Hannibal, who set the fires of war raging once again.

The Second Punic War (218–201 BCE) was made famous by Hannibal, best known for crossing the southern Alps with war elephants. Hannibal was a master of unexpected, and while Rome readied for a fight in Iberia in 218 BC, Hannibal slipped the Romans and led his troops on a grueling crossing through mountainous terrain previously thought to be unpassable. The Carthaginians entered the mountains with 50,000 men and 67 war elephants; they arrived in northern Italy with half their army and one elephant remaining. Hannibal faced two quick battles on the Ticino and Trebia rivers, where his tactical genius and superior Numidian cavalry were on full display. The Carthaginian army then marched down through the Apennine Mountains, suffering further casualties and desertions, before emerging in central Italy on the banks of Lake Trasimene. The Carthaginians ambushed the Romans along the northern bank of the lake, pinning them between the water and the previously hidden Carthaginian army now descending from the hills. 30,000 Romans were killed or captured, including the Roman consul for the year.

Despite this stunning success, the high-water mark of the Carthaginian campaign in Italy was still to come. Hannibal’s coup de grâce at Cannae (216 BCE) brought the Roman Republic to the brink of collapse and heralded in a period of near-hysterical panic that would forever after be known as Rome’s darkest days. On the open plains of southeastern Italy, Hannibal managed to totally envelop the Roman army despite having a much smaller force. 50,000 Romans were slaughtered in a single day, and in less than 2 years of fighting, Hannibal had killed or imprisoned 20 percent of Rome’s fighting force. But Hannibal chose not to march on Rome, and he would never get as good an opportunity to do so again. The conflict bogged down in a stalemate, with both sides refusing to give battle in unfavorable positions, and allied cities in Italy defecting and then being retaken in a brutal tug of war. After 15 years in Italy, Hannibal was finally recalled to Carthage to face a surprise invasion of Africa by Rome’s own brilliant young general, Scipio Africanus. The Battle of Zama (202 BCE) proved decisive. Exhausted and without an army in the field, Carthage surrendered. They were stripped of their overseas territories and forbidden to make war again.

Although thoroughly beaten, the Romans viewed Carthage’s mere existence as a threat. Cato the Elder was known to remark after every speech in the Senate: ‘furthermore, I consider that Carthage must be destroyed’. The final Punic War did just that. After a three-year siege of Carthage (149-146 BCE), the city was reduced to rubble, its population dead or enslaved, and salt sown in the ground so no city could rise to threaten Rome again.

The defeat of Carthage marks the beginning of the Roman Empire. The former Carthaginian territories were Rome’s first overseas acquisitions, and they flooded Rome with unprecedented riches and slave labor, beginning a golden age of Roman expansionism. But no matter how far removed from that brutal day at Cannae, the Romans never quite forgot how close they came to annihilation, when history had been poised on a knife’s edge of being re-written. Perhaps that’s why the great city of Carthage is remembered by history so well, the specter of possibility still looms, even so long after the ink has dried.

DAUGHTER OF CARTHAGE, SON OF ROME – Unexpected love in the midst of war in ancient Rome—a passionate story of conflicting loyalties, constant danger and fierce courage in the face of life-threatening risk.

Elissa Mago, a Carthaginian heiress, recklessly flees the prospect of a despised arranged marriage and arrives in Italy vulnerable yet defiant on the cusp of Hannibal’s audacious crossing of the Alps and invasion of Roman territory.

Marcus Gracchus, a brilliant and celebrated Roman Centurion, questions his own loyalty to Rome after his brother is murdered and he is ordered to serve under the leadership of the vindictive man who orchestrated his brother’s death.

A chance encounter thrusts the two together, first as captive and captor. But violence both on the battlefield and within the Roman legion eventually leads them into an alliance that is tested repeatedly by their ties to home. Ultimately, they must choose –their love for one another or their loyalty to their country.

Thanks Kate for this wonderful post. I don’t think many people understand how close Rome was to being destroyed by first the Etruscans and later the Carthaginians. You have to wonder ‘what if’ either had defeated the Romans.

Haven’t subscribed yet to enter into giveaways from my guests? You’re not too late for the chance to win this month’s book if you subscribe to my Inspiration newsletter for giveaways and insights into history – both trivia and the serious stuff! In appreciation for subscribing, I’m offering an 80 page free short story Dying for Rome -Lucretia’s Tale.

Haven’t subscribed yet to enter into giveaways from my guests? You’re not too late for the chance to win this month’s book if you subscribe to my Inspiration newsletter for giveaways and insights into history – both trivia and the serious stuff! In appreciation for subscribing, I’m offering an 80 page free short story Dying for Rome -Lucretia’s Tale.

Image 1: Hannibal’s invasion of Italy. Photo credit: Encyclopedia Britannica. “Hannibal” (1964) London: William Benton. pp. 65–67. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=3725763

Wow! What a great story, Kate. I hated history at school. If only they had taught us about these interesting people, cities and times. The ending of Carthage was a dreadful crime, by the sounds of it. And why did Hannibal use elephants?

Elizabeth: Welcome to the world of WW2!

Elephants were Hannibal’s tank corps. What better way to break the front of a Roman phalanx? Terrifying weapons, specially if you have never before seen one.

It would certainly have been a double surprise. An enemy coming across the Alps mounted on enormous exotic beasts.

What a fascinating time period–a wonderful setting for a historical novel!

Sounds like a great read. I love any time periods in historical fiction and non fiction.

I love this excerpt and am so excited to read it! I’ve read about Caesar to Nero, Augustus, Caligula. Super fascinating and exciting history. I love history and thank you for the article and chance to win a copy:(

Sounds like an amazing story!