My guest today is fellow Australian writer, Nigel Featherstone. His war novel, Bodies of Men, (Hachette Australia) was longlisted for the $60,000 2020 ARA Historical Novel Prize, shortlisted in the 2019 Queensland Literary Awards, and received a 2019 Canberra Critics Circle Award. His other works include the story collection Joy (2000), his debut novel, Remnants (2005), and The Beach Volcano (2014), which is the third in an award-winning series of novellas. He wrote the libretto for The Weight of Light, a well-regarded contemporary song cycle that had its world premiere in 2018. He has held residencies at Varuna, Bundanon, and UNSW Canberra at the Australian Defence Force Academy. He is represented by Gaby Naher, Left Bank Literary.

Remnants (2005), and The Beach Volcano (2014), which is the third in an award-winning series of novellas. He wrote the libretto for The Weight of Light, a well-regarded contemporary song cycle that had its world premiere in 2018. He has held residencies at Varuna, Bundanon, and UNSW Canberra at the Australian Defence Force Academy. He is represented by Gaby Naher, Left Bank Literary.

You can connect with Nigel via his website, Facebook, Twitter or on Instagram @ngfeathers. Bodies of Men is available in various formats via Hachette.

You can enjoy an illustrated reading from Bodies of Men on the HNSA Youtube channel.

What or who inspired you to first write? Which authors have influenced you?

It was reading that inspired me to write. My mother was an avid reader – for a few years she worked as a Sydney bookseller – and every few weeks she would take my brothers and me up to the municipal library and we filled our library bags with books; sure there was a lot of Tintin and Asterix, but there were always novels. That was on top of what we read for school. To this day, especially when I’m reading something that has burrowed under my skin, I get flashbacks, or echoes, of my earliest literary experiences and I’m sure it’s because reading has been a part of my life since the beginning. Also, I think I wanted to do what the authors were doing: make up worlds and characters and situations; explore things, ask questions; document, share, communicate. I’m lucky that I went to a school that valued reading writing: we had creative writing classes until Year 10; I could have written for hours. In terms of influences, I love JM Coetzee’s novels – Disgrace is probably the novel I admire the most – as well as those by Kazuo Ishiguro, Sigrid Nunez, James Baldwin, and Andrew O’Hagan. I also greatly admire the Russians, especially Chekov and Tolstoy. Poetry is in the mix too, including Mary Oliver and ee cummings.

What is the inspiration for your current book? Is there a particular theme you wished to explore?

The writing of Bodies of Men started with wanting to explore different expressions of masculinity under military pressure. For decades now, Australia has been manipulating, simplifying and amplifying its military history, for, I think, nefarious purposes, by which I mean domestic nationalism. The story that the nation has been telling itself is that all those who have served in our armed forces down through ages have been golden children and could do wrong; in essence, it’s a myth. A number of historians/writers, including Dr Peter Stanley and Paul Daley, as well as the Honest History group in Canberra, have been revealing the truth. In 2013 I had the good fortune of spending three months as a writer-in-residence at the Australian Defence Force Academy at UNSW Canberra, during which I wrote the first draft of the story that would become Bodies of Men. Of course, novels can be about many things, and it turned out that I was also writing about the way love can offer refuge.

What period of history particularly inspires or interests you? Why?

I’m most interested in the more modern end of history, so perhaps from the mid-18th century onwards. That’s because I’m keen to better understand Australia as a concept and an idea. It is a privilege to live in this country, and on this country, and I feel extraordinarily fortune, but so much damage has been done. Having said that, the more I learn about First Nations histories, which, of course, go back much longer than most of us can imagine, the better I am as a human being.

What resources do you use to research your book? How long did it take to finish the novel?

As mentioned, the writing of Bodies of Men began when I spent a good chunk of time as a writer-in-residence at ADFA/UNSW Canberra. The campus claims to have one of the world’s best military libraries, so I was able to fill my days exploring the stacks – in a way, I was simply seeing what interested me, and anything to do with military strategy or politics did not. I spent weeks reading as diversely as possible: novels, memoir, non-fiction, and poetry; I also watched documentaries. Two books became very important: Bad Characters – Sex, Crime, Mutiny, Murder and the Australian Imperial Force by Peter Stanley (2010), and Deserter: The Untold Story of WWII by Charles Glass (2013). Yes, I wrote the first draft of my novel while I was on campus, but that was really just the start of the process. I ended up doing 40 drafts, rewriting and editing most of it by hand (as in pen on paper), and it was not published until 2019, so it took six years from original idea to book in hand. It was a rather messy process, probably because this was my first work of historical fiction, so I felt that I needed to write my way into the history and the story, finding the characters and the key narratives as I went. To a large extent, the first draft was ‘stream of consciousness’, a directed dream, if you like, which I then refined and refined and refined, until it started to become more coherent and cohesive.

As mentioned, the writing of Bodies of Men began when I spent a good chunk of time as a writer-in-residence at ADFA/UNSW Canberra. The campus claims to have one of the world’s best military libraries, so I was able to fill my days exploring the stacks – in a way, I was simply seeing what interested me, and anything to do with military strategy or politics did not. I spent weeks reading as diversely as possible: novels, memoir, non-fiction, and poetry; I also watched documentaries. Two books became very important: Bad Characters – Sex, Crime, Mutiny, Murder and the Australian Imperial Force by Peter Stanley (2010), and Deserter: The Untold Story of WWII by Charles Glass (2013). Yes, I wrote the first draft of my novel while I was on campus, but that was really just the start of the process. I ended up doing 40 drafts, rewriting and editing most of it by hand (as in pen on paper), and it was not published until 2019, so it took six years from original idea to book in hand. It was a rather messy process, probably because this was my first work of historical fiction, so I felt that I needed to write my way into the history and the story, finding the characters and the key narratives as I went. To a large extent, the first draft was ‘stream of consciousness’, a directed dream, if you like, which I then refined and refined and refined, until it started to become more coherent and cohesive.

What do you do if stuck for a word or a phrase?

An interesting question! As noted above, I write by putting pen to paper, partly because that encourages me to compose rather than type, and partly it means I can be better connected to my body, which I know sounds rather odd but the more I practice writing the more I realise that it is a whole-of-body process, not just a brain process. So, if I’m stuck for a word or phrase, I try to listen more closely to what my body is telling me; it’s a matter of trying to feel my way to the right place – wait it out until there’s a tingle of electricity. Of course, I’m also a fan of the thesaurus and synonym dictionaries. My favourite of the latter is dated 1907.

Is there anything unusual or even quirky that you would like to share about your writing?

I think I just did! Perhaps the other odd thing is that I do like to wear certain clothes. My house is an old worker’s cottage dating from around 1895 and it’s either cool or cold for most of the year. This means that when I’m writing more often than not I need good, warm clothes, which involve ugg-boots, tracksuit pants, and a woollen jumper that my mother knitted for me and is 35 years old. If I’m not wearing that outfit, then I’m not in the right headspace. I also need silence – the idea of writing in a café does not appeal; in fact, it sounds hellish.

Do you use a program like Scrivener to create your novel? Do you ever write in long hand?

No, I don’t use Scrivener and never have. Writing by putting pen to paper is my preference. Having said that, I’m learning that typing has its place. Sometimes I type a scene or section very fast, just to see what that does to the prose – writing by putting pen to paper can result in too much detail and an over-emphasis on wordplay, whereby writing by typing can focus on the ‘and then and then and then’ of action. More recently I have been improvising scenes, especially when they comprise internal monologues, by speaking them aloud and recording them on my phone and then typing it all up verbatim, including the mistakes, just to see what’s there.

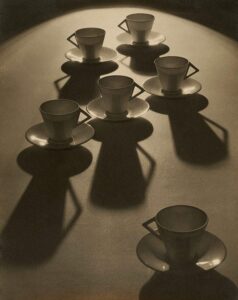

Is there a particular photo or piece of art that strikes a chord with you? Why?

Last year I read an extraordinary book called Olive Cotton: A Life in Photography, which is by Helen Ennis (2019). Olive Cotton was a wonderful Australian photographer, but for a time was married to Max Dupain so she was overshadowed by him, as was the way with these things (and perhaps still is). The image of Cotton’s that I love the most is ‘Tea Cup Ballet’, which dates from around 1935. As Ennis says in her book, despite the simplicity of the elements, the image is one of animation. I adore that. Perhaps, as a writer, I too am trying to use simple ingredients – words – to animate.

What advice would you give an aspiring author?

Tell the story that you’d love to see in the world. Perhaps a little more practically, when something good happens with your writing practice, you have 24 hours to celebrate: drink champagne, eat French Camembert, dance naked to terrible pop music in the lounge-room – but then you have to keep going. When something bad happens with your writing practice, you have 24 hours to commiserate: drink whiskey, kick furniture, cry – but then you have to keep going.

Tell us about your next book.

My next novel will be quite different, not historical fiction, though it will continue with my broad theme of exploring the trials and tribulations of living as well as possible despite the odds being stacked against us. At its core, Bodies of Men is a love story, and a family drama, and my next novel will stay in that general realm. I come from a complex family (don’t we all), and love, of all kinds, has been fraught (though there has been love), so I’ll probably spend my life exploring those things, because I doubt I’ll ever fully understand them. I’m also writing a play with songs – back in 2014 I was asked to write the libretto for a song cycle, which was such a thrilling experience (wild even) that I’m keen to write another piece for performance. Although there are similarities between writing for the page and writing for the stage, there are a heck of a lot of differences. Working in different modes helps to keep things fresh and exciting.

Egypt, 1941. Only hours after disembarking in Alexandria, William Marsh, an Australian corporal at twenty-one, is face down in the sand, caught in a stoush with the Italian enemy. He is saved by James Kelly, a childhood friend from Sydney and the last person he expected to see. But where William escapes unharmed, not all are so fortunate. William is sent to supervise an army depot in the Western Desert, with a private directive to find an AWOL soldier: James Kelly. When the two are reunited, James is recovering from an accident, hidden away in the home of an unusual family – a family with secrets. Together they will risk it all to find answers. Soon William and James are thrust headlong into territory more dangerous than either could have imagined. Bodies of Men is a beautifully evocative tale of two men whose lives are brought together in tragedy – for lovers of books by Kevin Powers and Sebastian Barry.

Thanks so much Nigel. Congratulations again on being longlisted for the ARA Historical Novel Prize. No mean feat!

Great topic and well done Nigel for the honest take on war valour and history. My father was in the Tobruk campaign and before that fought the Italian campaign. Very relevant. Jon

I enjoy reading many genres. Historical fiction is a favorite. Nigel’s book, Bodies of Men, is intriguing, particularly since I don’t know much about the war in the western desert. I relate to his love of reading. I too read from a young age. Writing in school was a given. In a college history class, I would read non-fiction historical books and then write first person reports – one of my favorite classes! I hope to be able to read this soon.

Sounds good. I love any genre that is historical fiction

A great interview. The 1907 synonym dictionary would be fascinating I’d say.

Interesting topic. Sounds like a good read in my favorite genre, historical fiction.

This sounds like such fantastic reading. I am adding to my list.